ART MADRID'25: TWENTIETH BIRTHDAY

The rain did not prevent the twentieth anniversary of Art Madrid from being celebrated in style at the Galería de Cristal of the Palacio de Cibeles. From the 5th to the 9th of March, the headquarters of the fair opened its doors to artists, galleries, collectors, art lovers and professionals of the sector to welcome us in an edition marked by a greater presence of women artists, more than 50% of debut artists, the presence of 34 galleries and around 1100 works produced between 2022 and 2025.

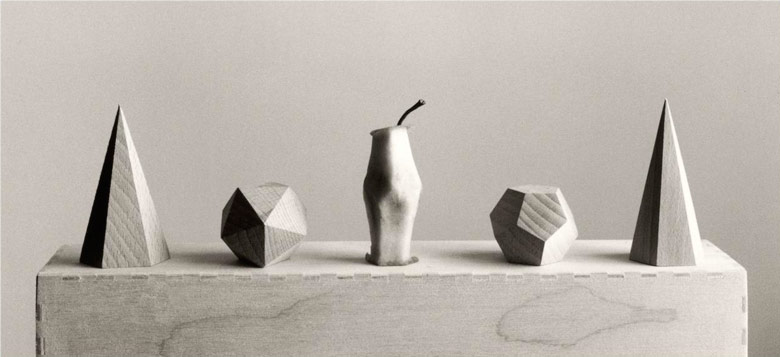

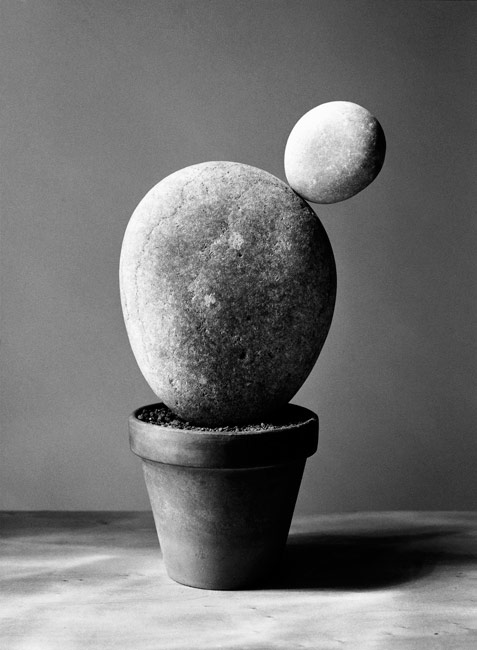

Art Madrid'25 opened its doors with a gallery program that included 34 exhibitors, 22 national, 12 international and 7 for the first time at the fair. More than 200 artists exhibited their most recent works, representing the latest artistic trends on the national and international scene. Painting with a relevant presence in all its forms of expression and representation; sculpture, photography, drawing, video and installation.

During these five days, Art Madrid'25 welcomed around 20,000 visitors, including collectors, professionals, the general public and new buyers.

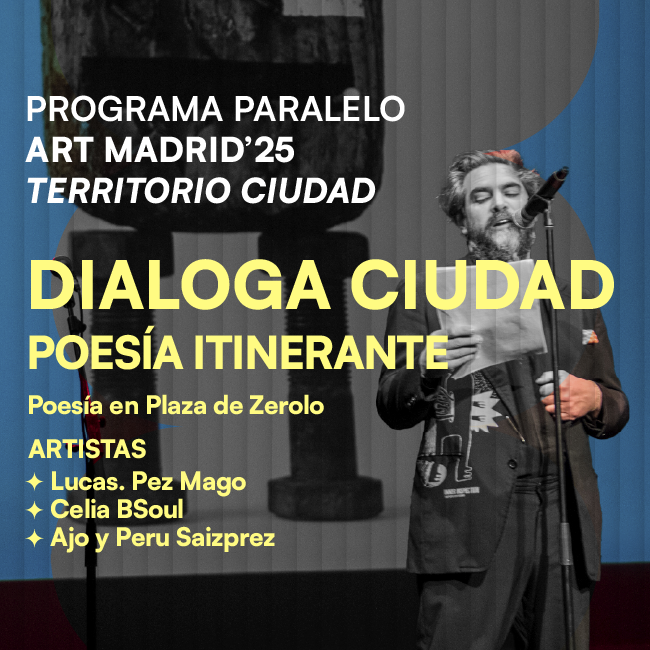

The celebration of this edition was accompanied by a parallel program focusing on the conceptual axis: Territorio Ciudad. In the run-up to the fair, from 28 February to 2 March, the following projects took place in the city of Madrid: Arquitecturas Imaginadas, Dialoga Ciudad and the second edition of La Quedada: Arquitecturas Imaginadas, Dialoga Ciudad and the second edition of La Quedada, a tour of studios and spaces for artistic creation. Arquitecturas Imaginadas transformed the metro into an ephemeral art gallery; Dialoga Ciudad filled the streets with poetry, establishing a direct dialogue with passers-by; while La Quedada opened the doors of artists' studios, allowing visitors to get a closer look at their creative processes. The week of the fair was also preceded by the Interview programme: Conversations with Marisol Salanova.

After the opening of the fair, the programme continued with innovative proposals such as Open Booth, a space created in collaboration with the University of Nebrija and Liquitex, which invited students from the university's Fine Arts department to present their work in a professional context. Similarly, the Raíces Afuera** cycle explored concepts of identity and belonging through performances that proposed different points of view and an extended reflection on rootedness and mobility in contemporary society.

Art in motion also played a prominent role in this edition, thanks to Cartografías de la Percepción, a video art programme curated by PROYECTOR that analysed the relationship between inhabitants and their urban environment through immersive audiovisual works. There was also 20 Grados**, developed at Espacio Tectónica, where ten artists used augmented reality, sound and performance to explore the interaction between architecture and its inhabitants.

One of the most innovative proposals in the edition was Ciudad Sutil by Susi Vetter, which transformed Montalbán Street into an interactive digital installation. This initiative transformed the public space and raised new questions about the relationship between people and their environment, inviting viewers to reflect on their impact on the urban landscape.

Around 30 artists were invited to participate in the parallel program of Art Madrid'25. An initiative that the fair's organisers intend to continue in future editions, with the aim of incorporating into the event other ways of supporting creation and encouraging dialogue between artists, the public and professionals in the sector, thus enriching the cultural experience of the fair.

PATRONAGE, PRIZES AND RESIDENCIES: PROMOTING CONTEMPORARY CREATION

One of the fundamental pillars of Art Madrid is its commitment to promoting art and supporting creators. Through its Patronage Program, the fair has consolidated its role as a platform for the promotion of emerging talent and the consolidation of artists in the market.

The Acquisition Award has enabled selected works to enter important private collections. This year, the Studiolo Collection, E2IN2 Collection and Devesa Law have chosen the works of Armando de la Garza (Acquisition Award. Studiolo Collection), represented by DDR Art Gallery; Fernando Suárez Reguera (Acquisition Award. E2IN2 Collection), represented by the Luisa Pita Gallery, and Moisés Yagües (Acquisition Award. Devesa Law), represented by the Aurora Vigil-Escalera Gallery; an initiative that ensures the dissemination and preservation of the works of the winning artists within the national collecting circuit.

For its part, the Emerging Artist Award, granted by One Shot Hotels as part of the One Shot Collectors program, has recognised the talent of Ana Cardoso, represented by Galería São Mamede. This recognition provides an important economic boost for the consolidation of artists in the development phase.

Finally, the Residency Award, organised in collaboration with DOM Art Residence and ExtrArtis, has been awarded to Luis Olaso, represented by Kur Art Gallery. Thanks to this award, the artist will enjoy an artistic residency in Sorrento, Italy, in August 2025, a unique opportunity for experimentation, cultural exchange and expansion of his artistic practice.

COLLECTING: THE ART OF ACQUIRING WITH CRITERIA

With the One Shot Collectors Program, sponsored by One Shot Hotels, the fair sought to promote the acquisition of works of art through a space for specialised advice. Under the guidance of expert Ana Suárez Gisbert, participants received guidance on how to start buying art or expand their collections with knowledge and criteria. This programme has made a significant contribution to strengthening the contemporary art market and strengthening the link between artists and collectors.

The twentieth edition of Art Madrid leaves behind sales figures that exceed those of the 2024 edition, with a total of 675 works acquired. Of these, 39 were acquired through the Art Madrid'25 Collecting Programme, led by art advisor Ana Suárez Gisbert. Ten per cent of the works exceeded the price of 20,000 euros; 15 per cent were pieces between 10,000 and 20,000 euros; 30 per cent were between 3,000 and 10,000 euros; and 45 per cent were works acquired for less than 3,000 euros. This confirms Art Madrid's role as a key event for those wishing to enter the world of collecting. In this latest edition, the fair has seen a greater influx of international visitors, as well as visitors from different regions of Spain, which confirms the growing interest of foreign collectors in adding works by Spanish artists to their collections. Once again, the galleries participating in Art Madrid have noticed an increase in the number of visitors and the interest shown by buyers, both experienced collectors and new enthusiasts who want to start collecting art.

AN EVENT MADE POSSIBLE BY ITS NETWORK OF PARTNERS

The success of Art Madrid'25 was made possible thanks to the support of its official sponsors: Liquitex, Lexus, One Shot Hotels, Safe Creative, Universidad Nebrija and Cervezas Alhambra. Their support has been fundamental in the celebration of Art Madrid's twenty years of contemporary art.

In addition, the fair has enjoyed the collaboration of cultural platforms and institutions such as **PROJECTOR, CRU Cultural Platform, Contemporary Art Collectors Association 9915, Colección Studiolo, E2IN2, DOM Art Residence, Devesa, Enviarte, Vanille Bakery Lab & Café and Pago de Cirsus.

It has also received the support of public institutions such as the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, the Madrid City Council, the Ministry of Culture and Sports, and the Madrid Community, strengthening its presence in the cultural scene.

In the field of dissemination, the media partners are: PAC, Gráffica, Cultura Inquieta, ArtPrice, Arte al Límite, Arte por Excelencias, VEIN, Art Facts and Bonart Cultural have contributed to the global project of the event.

ART MADRID: A FUTURE FULL OF POSSIBILITIES

After two decades of development, Art Madrid reaffirms itself as a dynamic, accessible and constantly evolving event. With more than 100,000 visitors in the last five editions, the fair has established itself as an essential reference in the national and international art scene.

The Galería de Cristal of the Palacio de Cibeles is once again the ideal setting for this celebration of contemporary art, a meeting place for galleries, collectors and artists from all over the world. With an innovative program and an increasingly open approach, Art Madrid'25 has shown that, after twenty years, its role in the artistic ecosystem is more relevant than ever, and its future is full of possibilities and new artistic explorations.

Thank you for joining us in this 20th edition of Art Madrid. Your trust and support are essential to continue promoting contemporary art and culture.

See you at Art Madrid'26!