GEGO AS A WEAVER, GEGO AS AN ARCHITECT OF SPACE

Oct 8, 2019

calendar

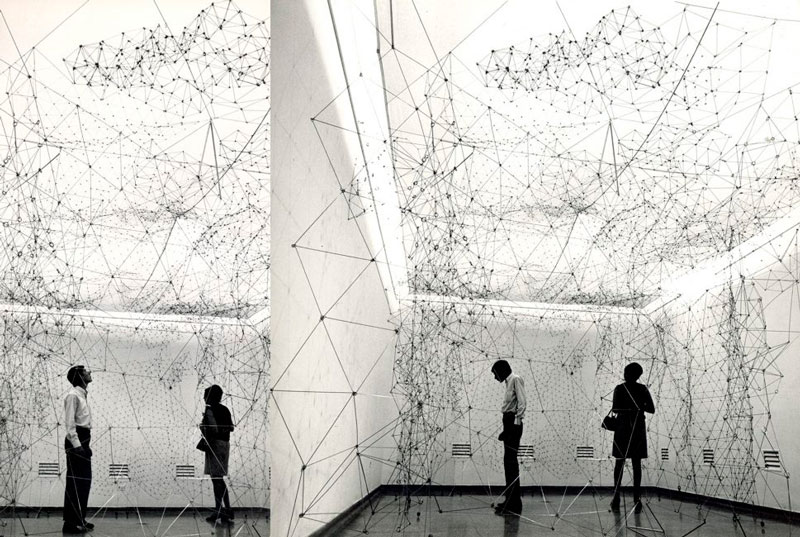

Like a meticulous and careful spider, the importance of manual work in Gego's pieces unfolds before our eyes and conveys ideas of deep meaning, such as the value of patience, contemplation, the observation of life in its many facets, the relationship with others, the cooperation. The simple approach of using metal segments as connectors between nodes and weaving huge interconnected networks, occupying a physical space, encloses a substantial visual and discourse load.

This German artist, based in Venezuela since she left her home country during World War II, began to develop her own language in the 1960s. In her work, it is evident the great influence of her training as an engineer, with a mention in architecture, studies that she concluded in 1938 at the University of Stuttgart. As Gertrud Goldschmidt, her real name, she developed her career in the world of design and architecture. She created a company dedicated to the manufacture of furniture and lamps and got involved in urban design projects with residential houses in Los Chorros, Quintas El Urape and Tulipán.

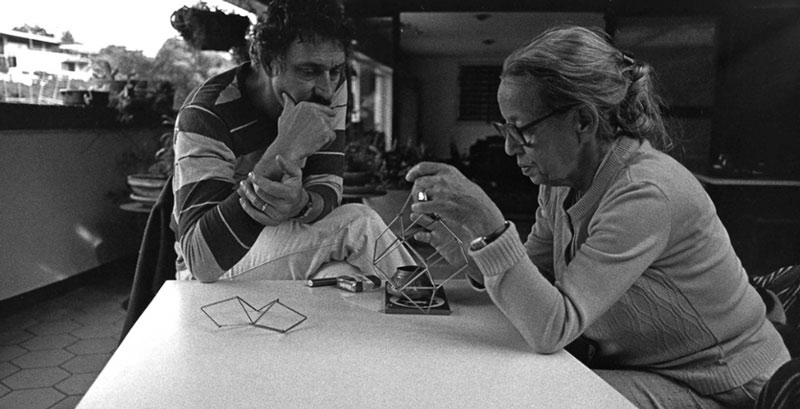

But since the late 50s, Gertrud ceases to be Gertrud and begins to be Gego. The take-off of her artistic career coincides with a turn in her personal life when, after having divorced her first husband in 1952, she meets her life partner for the rest of her days: Gerd Leufert. In the early years, her work becomes more landscape, expressionist and figurative; but soon she begins to explore concepts that interest her especially, such as the three-dimensional configuration of the works, at which time she establishes a relationship of friendship and mutual exchange with sculptors such as Alejandro Otero and Jesús Soto. In this period, called "Parallel Lines", the influence of geometric trends and kinetic art becomes palpable in many of her works, as with the piece "Sphere", which produces a surprising sensation of movement when one goes around it.

It was always crucial for Gego to include a spatial aspect in her work. Some of her most famous works belong to the well-known period of "Reticle-areas, Trunks and Spheres", which began in 1969. That's when the artist abandons rigid materials and begins to weave her nets in a flexible way using adaptable materials, and embraces new formats, always starting from pure forms, but open to the modification of patterns.

The undoubted influence of this artist on the kinetic movement and three-dimensional geometric art is undeniable. This has led the director Montenegro & Lafont to create 17 micro-documentaries with testimonials from personalities who know and value her work to offer us a more intimate vision of the author, a project entitled “fg conversations”. After she died in 1994, her family created the Gego Foundation, which has collaborated intensely on this proposal.

With several exhibitions to open at the São Paulo Museum of Art, the Jumex Museum in Mexico City, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona and the Guggenheim in New York, the Reina Sofia Museum organises a session to display the documentaries and open debate around the work of this artist, with the participation of Yayo Aznar (architect) and Guillermo Barrios (art historian), and presented by the curator and historian Federica Palomero. “Links in/about Gego”, Monday, October 14th, 2019 - 7:00 p.m. / Sabatini Building, Auditorium.