ART MADRID’26 INTERVIEW PROGRAM. CONVERSATIONS WITH ADONAY BERMÚDEZ

The work of Cedric Le Corf (Bühl, Germany, 1985) is situated in a territory of friction, where the archaic impulse of the sacred coexists with a critical sensibility characteristic of contemporary times. His practice is grounded in an anthropological understanding of the origin of art as a foundational gesture: the trace, the mark, the need to inscribe life in the face of the awareness of death.

The artist establishes a complex dialogue with the Spanish Baroque tradition, not through stylistic mimicry, but through the emotional and material intensity that permeates that aesthetic. The theatricality of light, the embodiment of tragedy, and the hybridity of the spiritual and the carnal are translated in his work into a formal exploration, where underlying geometry and embedded matter generate perceptual tension.

In Le Corf’s practice, the threshold between abstraction and figuration is not an opposition but a site of displacement. Spatial construction and color function as emotional tools that destabilize the familiar. An open methodology permeates this process, in which planning coexists with a deliberate loss of control. This allows the work to emerge as a space of silence, withdrawal, and return, where the artist confronts his own interiority.

In your work, a tension can be perceived between devotion and dissidence. How do you negotiate the boundary between the sacred and the profane?

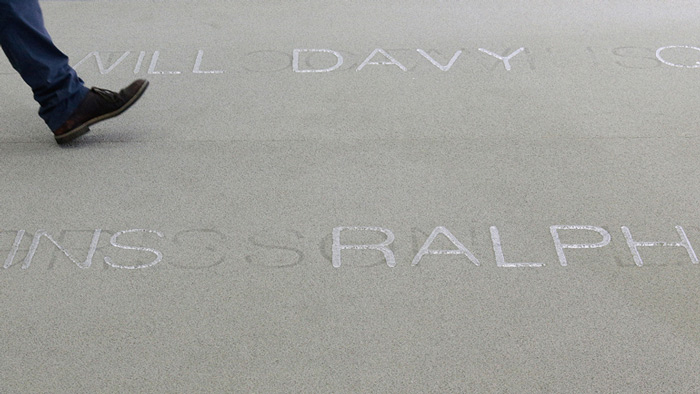

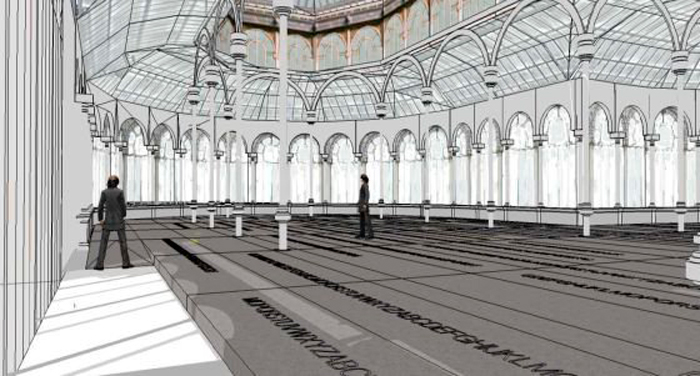

In my work, I feel the need to return to rock art, to the images I carry with me. From the moment prehistoric humans became aware of death, they felt the need to leave a trace—marking a red hand on the cave wall using a stencil, a symbol of vital blood.

Paleolithic man, a hunter-gatherer, experienced a mystical feeling in the presence of the animal—a form of spiritual magic and rituals linked to creation. In this way, the cave becomes sacred through the abstract representation of death and life, procreation, the Venus figures… Thus, art is born. In my interpretation, art is sacred by essence, because it reveals humankind as a creator.

Traces of the Spanish Baroque tradition can be seen in your work. What do you find in it that remains contemporary today?

Yes, elements of the Spanish Baroque tradition are present in my work. In the history of art, for example, I think of Arab-Andalusian mosaics, in which I find a geometry of forms that feels profoundly contemporary. In Spanish Baroque painting and sculpture, one recurring theme is tragedy: death and the sacred are intensely embodied, whether in religious or profane subjects, in artists such as Zurbarán, Ribera, El Greco, and also Velázquez. I am thinking, for example, of the remarkable equestrian painting of Isabel of France, with its geometry and nuanced portrait that illuminates the painting.

When I think about sculpture, the marvelous polychrome sculptures of Alonso Cano, Juan de Juni, or Pedro de Mena come to mind—works in which green eyes are inlaid, along with ivory teeth, horn fingernails, and eyelashes made of hair. All of this has undoubtedly influenced my sculptural practice, both in its morphological and equestrian dimensions. Personally, in my work I inlay porcelain elements into carved or painted wood.

What interests you about that threshold between the recognizable and the abstract?

For me, any representation in painting or sculpture is abstract. What imposes itself is the architectural construction of space, its secret geometry, and the emotion produced by color. It is, in a way, a displacement of the real in order to reach that sensation.

Your work seems to move between silence, abandonment, and return. What draws you toward these intermediate spaces?

I believe it is by renouncing the imitation of external truth, by refusing to copy it, that I reach truth—whether in painting or in sculpture. It is as if I were looking at myself within my own subject in order to better discover my secret, perhaps.

To what extent do you plan your work, and how much space do you leave for the unexpected—or even for mistakes?

It is true that, on occasions, I completely forget the main idea behind my painting and sculpture. Although I begin a work with very clear ideas—preliminary drawings and sketches, preparatory engravings, and a well-defined intention—I realize that, sometimes, that initial idea gets lost. It is not an accident. In some cases, it has to do with technical difficulties, but nowadays I also accept starting from a very specific idea and, when faced with sculpture, wood, or ceramics, having to work in a different way. I accept that.