AFRICAN ART: FROM THE OUTSIDE

Jan 4, 2023

art madrid

The network in which contemporary artistic practices are produced is a time and a place frenzied, something like an ever-expanding entropy. However, in such a "disorder", valuable intentions are appreciated for those who consume the search for the multifaceted and not circumscribed to a finite space such as geography.

For the Senegalese poet Léopold Sedar Senghor, blackness is a term that contains a duality of objective and subjective signifiers; it is the conjunction of values of the civilization of the black world, and it is also how each black or black community lives the values of their society. The virtuosity/responsibility with which this intangible asset can be built from aesthetic and artistic-visual platforms could be located, for example, in the city of Sitges, outside of Africa, but respecting the essence of values that have transcended a generation to another, in the search for narratives and exercises that claim alterity and break with the schemes that a type of exotic primitivism has haunted the work of African artists or those of African descent for centuries..

Out of Africa (OOA), founded in 2011, is one of the galleries participating in the 18th edition of Art Madrid. With an extensive list and an endless journey through the representation and promotion of African artists and those of African descent, it proposes an approach to the works of four of its creators: Megan Gabrielle Harris, Médéric Turay, Rémy Samuz, and Oliver Okolo. Maintaining its desire to defend the production of contemporary African art, Out of Africa offers an exhibition platform for emerging and established artists to express their respective narratives, values , and experiences through their creative proposals. The gallery provides support and visibility to the exploration, growth, and professionalization of decolonial practices in its curatorial discourses.

The exhibition proposal that brings the works of these four artists presents various currents and manifestations, among which portraiture, figuration, sculpture, and abstract expressionism stand out. Each one of them follows a personal line of work in which they explore media, themes, and narratives that invite debate on identity, the exploration of individuality and the evocation of the senses; proposals that gravitate around a type of revealing emotion that stands out from the hegemony of the conscious and the everyday.

Megan Gabrielle Harris, (Sacramento, United States, 1990) is a Nigerian descent creator who works between California, New York and Cape Town. In her works, the presence of the female figure is the central theme. And her landscapes in acrylic on canvas reproduce a free female figure every time empowered and sure of her place in the contemporary equation. The psychological treatment of others and herself, the approach to other bodies and her own, move away from the conventions with which black women have historically been identified. The voice of self-recognition imbues her portraits and self-portraits with a liberating force; Megan Gabrielle Harris' paintings are a social vehicle to generate present awareness about how the African female subject has been represented for centuries. Her research tries to break with the codes of association that place the black African woman at the center of a constrained and disrespectful vision, linked to a role imposed by a patriarchal society, which subjugates and exploits their physical bodies and degenerates their spiritual self.

The artist places the woman at the center of some landscape compositions, with earthy colors that fade into the background and impregnate the female presence with even more visual force. As if it were a spinal column, the women portrayed appear with their imposing hair in the center of the composition: confident, challenging, receptive and contemplative... In this way, she manages to recreate scenarios of individuality in outdoor spaces, in fugue postures, with their back to the viewer and even imitating the occasional conventional portrait, so common in the history of Western art but that she simply could not even have imagined in the past. Harris's work ponders the freedom of expression that women have achieved in some parts of the world and that, in others, is still a struggle to wage.

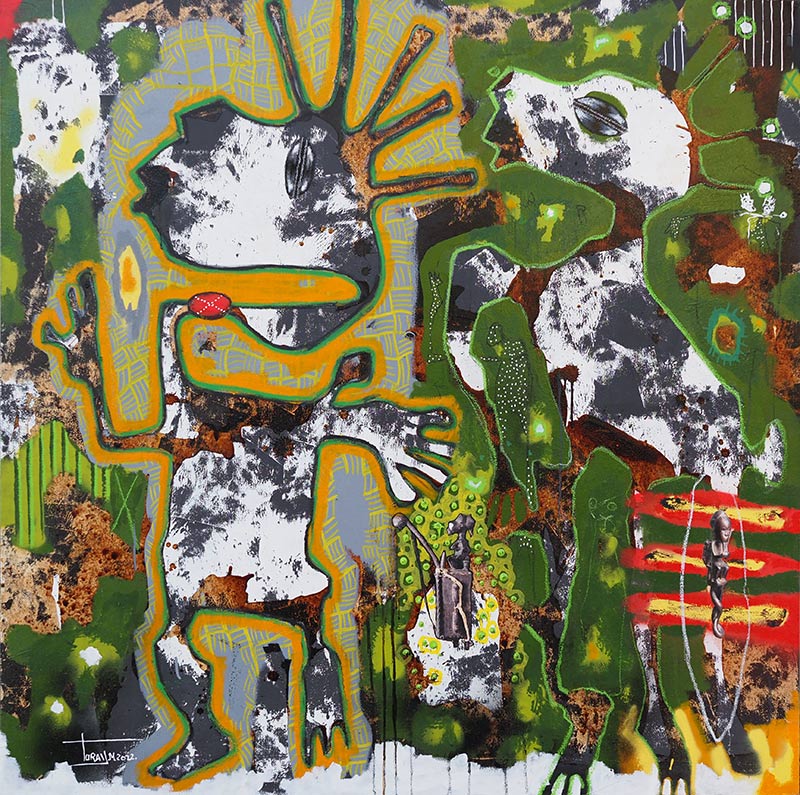

Médéric Turay, (Abidjan, Ivory Coast, 1979) currently lives and works in Marrakech, Morocco. He is a multidisciplinary artist inspired by abstract-geometric figuration, with a mixture of that cosmogony that roots the artist in his ancestral past. Turay has a vast reservoir of knowledge from his experiences in various parts of the world. His training indebted to hip-hop music, the graphic novel and his incessant travels through the United States and Africa, provoke an experiential connection in his work. When the viewer finds itself in front of his pictorial entities, sometimes figurative, other times abstract, and permanently impregnated with a complex visuality and a strong spiritual nuance. The artist preserves and cultivates his roots through ancestral masks and symbols, typical of Akán, in West Africa, a town from which he derives this heritage that connects with the vital forces that drive the human being.

Attempting to break away from the racial, social, geographic and political, Turay founds a type of expanded performative painting in which the intrinsic forces of the self are balanced in the symbols of the cross and the spiral. Stability and dynamism, rectitude and fertility, turn his characters into messengers of a cosmogony in which the past, present and future coexist.

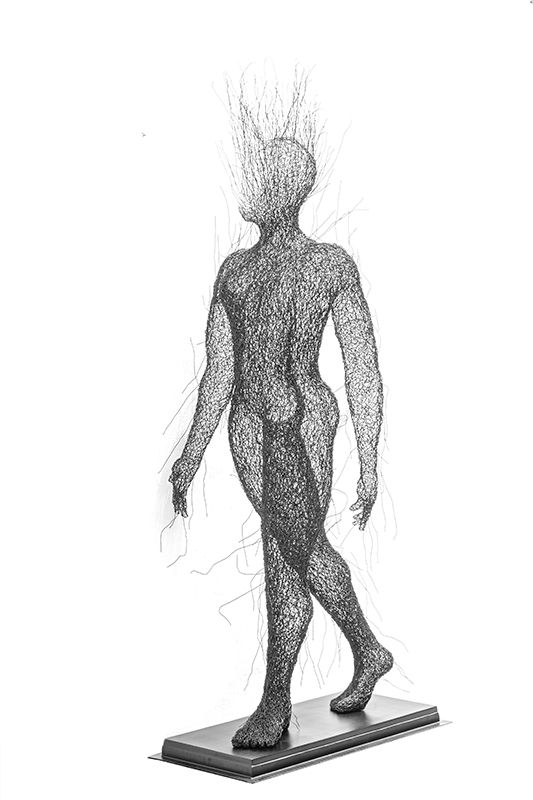

Rémy Samuz, (Cotonou, Benin, 1982) currently lives and works in his hometown. His sculptures fulfill the desire of many artists to humanize their inert creations with a breath of life. The visual force that accompanies his metal fabrics began when, being just a child, he dedicated himself to modeling miniatures of characters that, at that time, were a mystery to those around him. His artistic training, accompanied by specialization in metallurgy, has led this artist to master the technique of weaving iron wire almost perfectly. The rigidity of the metal does not prevent him from "having fun" conceptualizing sculptural works that address vast notions about family, freedom, identity, happiness, and love.

Oliver Okolo, (Suleja, Nigeria, 1992) lives and works in Abuja, Nigeria. Self-taught, he is a young artist who has found a way to develop his creative universes in the representation of the human figure. The veil with which conflicts and social problems tend to overlap builds the narrative that the artist then pours onto the faces of his protagonists. Apparent calm, ease, indifference, and some vestiges of alienation, are ideas that can confuse the viewer in that fine-drawn and intelligent criticism that the artist recounts in his men and women peacefully located in calm settings. The absence of chaos, love in the air, the green sky, and the yellow, orange or blue are semantic keys to activate the presence of tension in the faces of the figures that provoke the viewer. The apparent simplicity of the portrait achieved with ease and realism supports the expressive capacity that Okolo works with both the versatility of charcoal and the textures he performs with the brush. The search for technical perfection is one of the artist's obsessions who is committed to using his references in a type of work that dialogues with otherness and proposes an updated reading of what is inherited in contemporary times, and that is part of a time expanded and not in an immovable territory.

Four African and African descent artists come to Art Madrid in this edition with an intrepid exhibition proposal that breaks into the scene of national production to build a story about identity, the foundation of the emerging, and the urgency of an unprejudiced look at African artistic production. The aesthetic and formal quality will not overlook its presence in the exhibition area. These makers own a historical reason that reminds us that from the outside, we can also appreciate the truth of others.