Each edition of Art Madrid is, above all, an exercise in observation. Rather than a closed declaration of intent, it functions as a space where different artistic practices coexist and enter into dialogue, reflecting the moment in which they are produced. In 2026, the fair reaches its 21st edition, consolidating an identity grounded in plurality, close attention to artistic practice, and the coexistence of diverse languages within a shared curatorial framework.

In this context, Art Madrid’26 does not present a single dominant aesthetic or a unified narrative. What unfolds in the Galería de Cristal of the Palacio de Cibeles is a broad and varied landscape, shaped by the proposals of national and international galleries working with artists whose practices respond—each from very different positions—to shared questions: how to continue producing images, objects, and discourses in a saturated context; how to engage with tradition without becoming trapped by it; and how to make the contemporary visible without falling into the ephemeral.

This text offers a reading of the aesthetic currents running through the fair, understood not as closed categories but as lines of force. These currents help to clarify what visitors will encounter and from which coordinates a significant part of contemporary artistic production is emerging today. This approach is rooted in one of Art Madrid’s core principles: respecting the DNA of each exhibitor while fostering a plural creative ecosystem capable of reflecting the richness and diversity of the current artistic landscape.

One of the most consistent features of Art Madrid’26 is the attention paid to materiality. Painting, sculpture, and works on paper are presented as spaces where material is not merely a support, but an active element within the discourse itself.

Many of the works draw on traditional techniques—oil, acrylic, graphite, ceramic, or wood—but are approached with a fully contemporary awareness. Surfaces become sites of accumulation, erosion, sheen, or density. Gestures remain visible, and the construction of the work is embraced as an essential part of each artistic language.

This emphasis on materiality does not stem from nostalgia for craftsmanship, but from a desire for presence. In contrast to the relentless circulation of digital images, these works demand time, close viewing, and physical attention. Rather than seeking immediate impact, they invite a slower and more sustained relationship with the viewer.

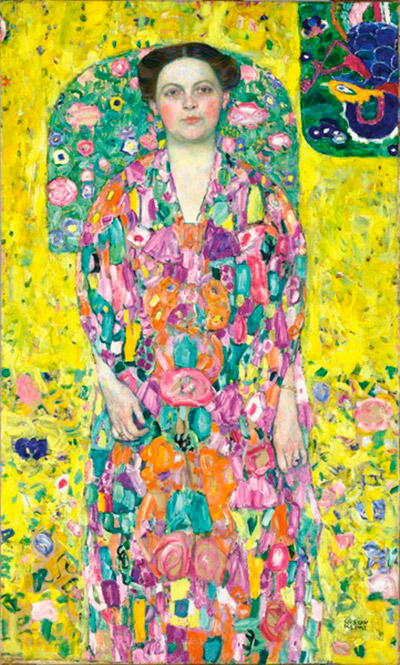

Painting occupies a central place within the fair, though it does so from highly diverse positions. This is not a return to academic models, nor a rejection of contemporaneity, but an expanded understanding of painting—open to the incorporation of other materials and visual languages.

Works appear in which oil coexists with spray paint, collage, resins, or graphite; surfaces where the pictorial merges with the object-based; images that move between abstraction, fragmented figuration, and symbolic reference. Painting is understood here as a flexible field, capable of absorbing influences from urban art, design, photography, and archival practices. For visitors, this results in a journey where painting is not presented as a homogeneous language, but as a territory of constant exploration shaped by varied and enriching formal decisions.

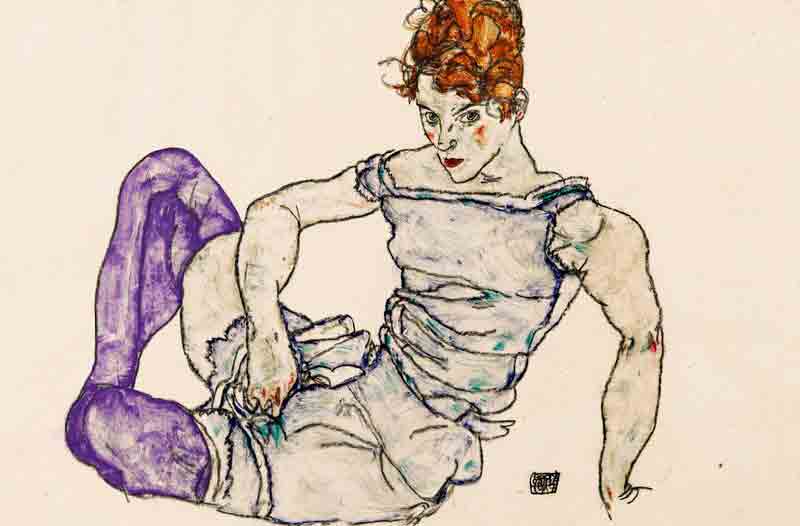

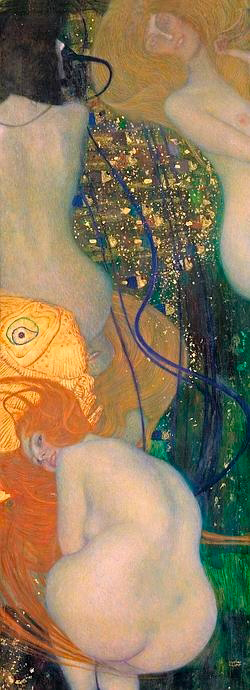

Rather than fading away, art history emerges at Art Madrid’26 as an active working material. Some proposals engage directly with classical iconographies or traditional genres such as portraiture, still life, or historical scenes, but do so from a critical and displaced perspective.

These works do not aim to reproduce past models. Instead, they place them under tension by altering context or scale, introducing unexpected elements, or foregrounding aspects that today appear problematic or revealing. Tradition is approached not as a fixed canon, but as an open archive—one that can be revisited, questioned, and rewritten. This dialogue resonates both with viewers who recognize historical references and with those who encounter them through a contemporary lens, aware that images of the past continue to shape how we understand the present.

Another defining thread of Art Madrid’26 is the dissolution of boundaries between disciplines. Many works resist classification within a single category, operating simultaneously as painting and object, sculpture and drawing, image and structure.

This hybridity reflects a contemporary context in which artistic languages no longer function in isolation. The resulting works call for open-ended readings, where form, material, and idea interact without fixed hierarchies, encouraging viewers to navigate meaning through experience rather than predefined frameworks.

Drawing and works on paper hold a significant presence in this edition. Far from being understood as preparatory or secondary, many of these pieces function as autonomous works—precise, deliberate, and conceptually robust.

Through lines, grids, voids, and repetitions, artists construct images that explore territory, memory, architecture, and the body. An economy of means does not diminish complexity; instead, paper becomes a space for visual thinking, where the passage of time and the trace of gesture are clearly registered. These works introduce a slower rhythm into the fair, inviting moments of pause and attentive observation.

Sculpture occupies an especially meaningful position at Art Madrid’26, situated between the organic and the structural, and between artisanal processes and industrial solutions. The use of recycled wood, ceramics, metals, and synthetic materials is not merely technical, but conceptual—prompting reflection on materiality, time, and transformation.

These pieces emphasize form, balance, and spatial relationships, understanding sculpture as a body that engages in dialogue with its environment and with the physical presence of the viewer. Often presented as symbolic objects rather than narrative devices, they activate open fields of association where meaning emerges through experience rather than explanation.

Alongside more gestural and material-based approaches, the fair also includes works grounded in geometry, pattern, and structure. Built upon precise visual systems, these pieces employ repetition, symmetry, and modulation to generate rhythm and tension.

They offer a counterpoint of restraint and formal control within the broader context of the fair, expanding the aesthetic spectrum and underscoring the diversity of contemporary artistic approaches.

Many of the works presented articulate non-linear narratives composed of symbols, cross-references, and deliberately ambiguous spaces. Rather than offering closed stories or singular interpretations, they function as open images—points of activation that invite interpretive engagement.

This approach reflects a contemporary sensibility that challenges the notion of fixed meaning, shifting part of the responsibility for interpretation onto the viewer. The artwork becomes a space of negotiation, where memory, experience, and perception actively shape understanding.

The body of work brought together in this edition reveals a sustained engagement with matter as a site of reflection and meaning-making. In the face of increasingly rapid and dematerialized modes of production, these works reaffirm the value of material support, process, and time as fundamental elements of artistic practice. This shared orientation does not define a single aesthetic, but establishes a common ground where diverse practices converge around the need to anchor artistic experience in the tangible and the constructed. Within this context, Art Madrid consolidates itself as a meeting space where contemporary art is presented with critical awareness, rigor, and clarity—fostering an active relationship between artwork, artist, and audience.